When studying historical documents, it’s fascinating to observe that regardless of how a statement was received at the time it was delivered, messages of truth, integrity and greatness endure through the ages.

When studying historical documents, it’s fascinating to observe that regardless of how a statement was received at the time it was delivered, messages of truth, integrity and greatness endure through the ages.

My French class and I recently examined two speeches of note that were made on June 30, 1960, the day the Congo won its independence.

King Baudouin of Belgium delivered an address stating how his predecessor King Leopold II began a great work, liberating the Congolese from slavery, and how the Belgians had done such an amazing job developing their colony. He warned the people not to be too hasty to replace the existing structures and implied that the Belgians would be there to continue to help run the new state.

It was, quite frankly, the epitome of a paternalistic narrative, steeped in colonialist mythology and outright lies. It would be naïve to believe that Baudouin was ignorant to the fact that Leopold II had claimed the Congo Free State as his personal plantation and was responsible for millions of deaths.

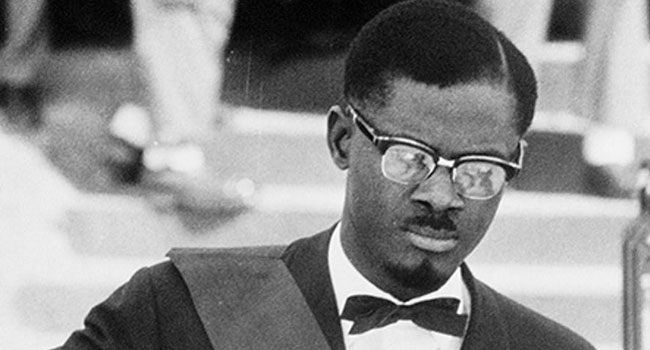

Baudouin was followed by the first prime minister of the Congo, Patrice Lumumba, who delivered a largely impromptu speech. Though it was called a “venomous attack” by Time magazine, one is left to wonder if the writer of these words even understood French.

Lumumba’s words are as rich, honest and contemporary today as when they were first spoken. He pointed out that there was no freedom and no justice under the Belgians. Congolese were beaten, insulted and forced to do backbreaking work. They were forbidden to go to the same cinemas and restaurants, they were not adequately paid, and they were expected to use the formal “vous” when speaking to white people while being addressed with the informal “tu” in return.

It may be difficult for those who haven’t spent time in the Congo to understand the depth of these inequalities.

In the 1990s, I lived in the capital Kinshasa, a city the Belgians had the audacity to name Leopoldville. I was shocked when my Congolese friends pointed out the parts of the city Africans couldn’t enter without a pass during colonial times. I was confused when some of my colleagues wouldn’t address me as “tu” even when I asked them to, or when people expressed surprise as I performed manual tasks.

Perhaps these points in his discourse could have been forgiven had Lumumba not been an idealist. He made it clear that foreigners were welcome but he asked for a co-operation that would be financially beneficial to the citizens of the Congo. Lumumba also believed in a pan-African vision and called on the people of his country to live together in peace.

This took place during the Cold War, and Lumumba’s most egregious thought in the eyes of capitalist powers was his willingness to work in a spirit of mutual respect with anyone who was willing to do so, even the Soviets.

Within months of his inauguration as prime minister, Lumumba was a hunted man. The Belgians stoked the flames of tribalism, as colonial powers so often did, and dashed Congolese hopes of a unified country. Lumumba was arrested and murdered in a co-operative effort between Congolese factions, Belgians and Americans on Jan. 17, 1961.

To its credit, Belgium apologized for its part in this murder in 2002. The country has also recently begun the process of reconciliation with the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and there’s a growing sentiment in the country to support fair reparations.

Lumumba was not a simple idealist. He was a visionary. He recognized the truth of an unjust world and saw how it could be better.

Even 60 years after his death we can see the world he dreamed of, a world that honours the martyrs who died at the hands of Western colonialism, the kind of world we so drastically need to build today.

Troy Media columnist Gerry Chidiac is an award-winning high school teacher specializing in languages, genocide studies and work with at-risk students. He also teaches French at UNBC.

For interview requests, click here. You must be a Troy Media Marketplace media subscriber to access our Sourcebook.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.