From Wilson to Roosevelt to Kennedy and Reagan, Americans have long been kept in the dark about their Presidents’ health

When Donald Trump was struck with COVID-19 several weeks before the 2020 election, I wrote a column about the implications of presidential health and the historical tendency to cover up problems. The controversy around the fitness of President Joe Biden brings the issue back to centre stage.

When Donald Trump was struck with COVID-19 several weeks before the 2020 election, I wrote a column about the implications of presidential health and the historical tendency to cover up problems. The controversy around the fitness of President Joe Biden brings the issue back to centre stage.

Although the 2020 column focused on the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, he wasn’t the first American president with such issues.

Woodrow Wilson suffered a stroke in October 1919, the severity of which was hushed up by a small internal circle headed by his wife, Edith Wilson. In fact, she served as an unofficial chief of staff, determining which cabinet papers her husband would see and often summarizing the key points to facilitate his understanding. The term she later used to describe her role was “stewardship.”

As for Roosevelt, he was a much sicker man than anyone let on when he ran for an unprecedented fourth term in 1944. His doctors believed that, if elected, he’d die in office. But while his diminished capacity was clear to those around him, substantial efforts were made to keep it from the general public.

Photo by History in HD |

| More from Pat Murphy |

| Could the UK Labour landslide be the death knell for the Conservatives?

|

| Who Is Pierre Poilievre really?

|

| Civilian casualties are a tragic reality of war

|

As events transpired, Roosevelt’s doctors were right. He died in April 1945, just weeks into the new term. And it remains a matter of historical conjecture whether his depleted condition impacted the outcome of the February 1945 Yalta conference – which effectively ceded Eastern Europe to Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union.

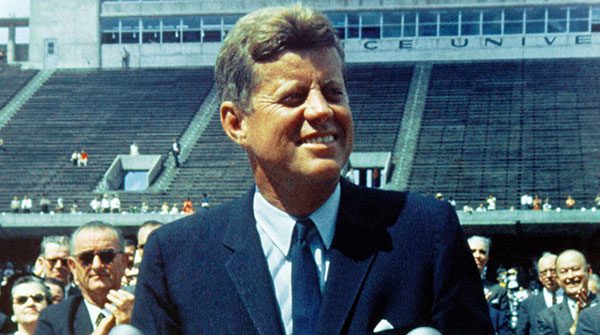

Wilson and Roosevelt lived in a world before the advent of nuclear weapons considerably upped the ante with respect to presidential impairment. That wasn’t the case with John F. Kennedy.

Kennedy’s underlying health was always precarious. Contrary to the cultivated image of robust vitality, he was beset by an array of maladies requiring a regular drug cocktail, which he supplemented from time to time with amphetamines. And there was his back, ever fragile and chronically painful, so much so that he sometimes resorted to getting around on crutches when away from the cameras.

Given the razor-thin closeness of the 1960 election, it’s an open question whether Kennedy would’ve been elected if the true state of his health had been widely understood. Still, it’s fair to say that his issues didn’t prevent him from doing his job.

His back pain during the June 1961 Vienna summit with Nikita Khrushchev certainly didn’t help him make a positive first impression. Speaking to American journalist James Reston after the summits’ second and final day, Kennedy described it as the “roughest thing in my life.” Khrushchev, he said, “just beat the hell out of me.”

But while Khrushchev’s negative assessment encouraged him to launch a number of actions culminating in the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy’s deft handling of the crisis was close to exemplary.

There was also Ronald Reagan.

Although a seasoned and adept debater, Reagan’s performance during the first 1984 presidential debate with Walter Mondale was atypically lacklustre, an impression significantly compounded by his visibly losing his train of thought in the final moments. Two days later, the Wall Street Journal ran a front page story headed “New Question in Race: Is Oldest U.S. President Now Showing His Age?”

Then about halfway through his second term, there were concerns about the degree to which the Iran-Contra scandal had affected his focus and morale. One aide even privately suggested invoking the 25th Amendment to remove him on the grounds of incapacity.

However, nothing came of it, and the second Reagan term racked up a series of significant successes. There was tax reform, immigration reform, and – most important – a major breakthrough in relations with the Soviet Union.

Understanding this success requires appreciating the particular team dynamic of Reagan’s governing style. It was an absolutely essential part of the formula.

Generally a big-picture guy, Reagan was often detached from operational details. With some exceptions – such as his deep involvement in the Soviet negotiations – his role was to establish general principles, sign off (or sometimes not) on proposed decisions, and decide on pragmatic compromises when necessary.

And, of course, there was also his compelling role as public articulator and persuader, a leadership dimension in which he was unusually blessed. Even as he visibly aged, Reagan never lost that capability.

One more thing.

At the start of his second term, Reagan was just shy of his 74th birthday; Biden would be 82. Those of us of a certain age suspect that might constitute a meaningful difference.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.