There’s nothing simple about the story of Canada’s Indian Residential Schools. The system underwent considerable change during its 126-year history, with fluctuations in size, focus, and influence.

There’s nothing simple about the story of Canada’s Indian Residential Schools. The system underwent considerable change during its 126-year history, with fluctuations in size, focus, and influence.

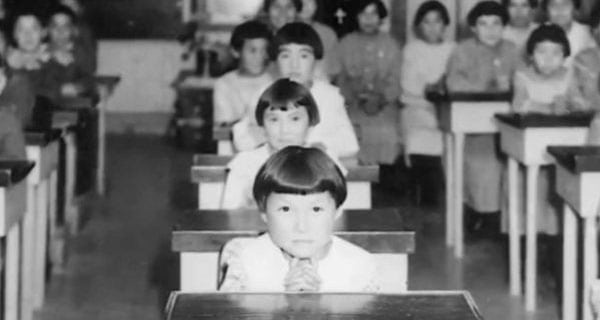

Beginning as a collection of industrial schools and later transformed to the residential school model, the system had its origin in one school established in 1833 as part of the St. John’s Mission in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., became a system of industrial schools and, later, residential schools under the newly-formed government of Canada, grew to a maximum of 86 schools in 1960, then shrank again until the last one closed in 1996.

At different times, the system operated under quite different mandates, policies and funding practices. Different religious organizations from a number of Christian denominations provided staffing and funding, and the schools served many native communities in quite different ways.

Individual schools saw very different teachers, counsellors, and administrators come and go, and Canadian attitudes regarding Indigenous people evolved.

Over time, some schools came to resemble less the Dickensian workhouse and more a regular boarding school.

But the general public knows little of this complexity. What finds its way into the public consciousness is an encapsulated version, often focusing on the more sensational aspects: helpless young people tormented physically and sexually, the sometimes brutal repression of vital native culture, and the misery of children torn from the arms of their parents by Indian agents or RCMP constables.

Reports of secretive burials of children who died while in a residential school have sparked public outrage.

Cultural repression, abuse of all kinds, forcible incarceration and even preventable deaths did happen, and a system that should have done far more to prevent such things can rightly be condemned.

But the facts show that they happened much less frequently than is commonly believed, and arguably had much less effect on First Nations communities than has been confidently stated. The ‘accepted fact’ is in truth a convenient myth.

Sadly, nearly all media reports focusing on the challenges facing First Nations people routinely point to the residential schools as a major cause. Almost without fail, the system and its intergenerational effects are blamed not only for the education deficit but also for the poverty, drug and alcohol addictions, high unemployment, and disproportionate rates of suicide.

Like most mythical narratives, this one contains a kernel of fact, and like all myths, it serves to satisfy some compelling need or desire on the part of those who cling to it.

First Nations leaders refer to it in the belief that it generates feelings of guilt and sympathy in the Canadian public, assisting native efforts to bring about badly-needed changes.

The federal government makes no denial — and even apologizes — because the schools conveniently existed at far remove from their current administration, and provide a handy explanation for ills that still beset our First Nations people. Blaming the system deflects attention from far more damaging and continuing government policy, action and inaction.

The Canadian public, equally eager to shift the blame for current ills onto something so safely in the past, is prone to accept the oft-repeated claims about the horrors of residential schools and the lingering legacy.

But surely there are Canadians who think public policy should be based on firm evidence rather than emotional, widely-promulgated but demonstrably inaccurate stories.

Far more significant factors have created – and perpetuate – the many problems faced by First Nations people today. They include the underfunding of native education generally, the government’s repeated failure to observe treaty obligations, and a variety of other misguided federal policies. These last include the failure to consult meaningfully with native groups regarding issues that affect them significantly, the 67-year ban on such important gatherings as the Sun Dance and the potlatch, and the rush to place native children in provincial schools in the 1950s.

And the finger-pointing should not just be directed at Ottawa. The rapid spread of non-Indigenous culture through technology has likely done more to erode First Nations culture and community life than any efforts by Christian missionaries.

As government records clearly show, the great majority of First Nations children were never enrolled in a residential school.

And while some students lived in a residential school for as many as 12 years, others were enrolled for far shorter periods, some for only one or two years. The average enrolment period was about 4.5 years.

And for most of the years in which the system operated, between 10 and 15 per cent of residential students were absent on any given day. Day school attendance was far worse.

Even when family allowance payments in the 1950s led to a Canada-wide increase in public school attendance, the federal day schools reported higher rates of absenteeism than provincial public schools.

And things have not improved considerably. A 2012 Edmonton Journal article reported that “In total this school year, 17,954 children and young adults age four through 21 living on reserves in Alberta are either in school or have earned their high school diploma. Another 11,699, or 39 per cent of children and young adults, have dropped out or were never registered.”

Little or no education must certainly be considered a major cause of poverty, its related social ills, and all kinds of negative intergenerational effects.

As for the negative intergenerational effects of residential school attendance, a 2010 Statistics Canada study that examined native language use by First Nations children living off-reserve found that those who had attended a residential school were no different in their use of their native language than those who had not.

The 2006 Aboriginal Children’s Survey shows that older First Nations people — a segment of the population who are more likely than younger people to have attended a residential school — have more use of their native languages than their children or grandchildren.

Moreover, at least one credible survey reports that former students of residential schools are nearly twice as likely to have retained more of their language and traditional culture than those who did not attend an institution, and are more likely to provide leadership in preserving that culture, than those who did not attend.

Little or none of this emerging evidence appears in the media upon which Canadians depend for information and informed comment.

Even the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has helped spread erroneous information. At the final National Gathering in Edmonton, one of the commission’s information displays stated that, after 1920, criminal prosecution threatened First Nations parents who failed to enrol their children in a residential school. This is simply a falsehood.

Let’s be clear. The system was a deeply flawed attempt to accomplish two main objectives: give native children education and training that would help them survive economically and socially in a white man’s world, and to eradicate those aspects of native culture that would hold them back from achieving those goals.

As is now perfectly obvious, it failed to do either.

Moreover, the system was funded and administered in such a way as to allow an unconscionable amount of neglect and abuse of vulnerable young people.

But recognizing the system as a bad one should not have us wildly exaggerating its failures, demonizing it, and allowing it to distract us from far more serious threats to First Nations individuals and communities.

As long as the myth of the Indian Residential School continues to be used as a scapegoat for 200 years of land appropriation, cultural invasion, deprivation, marginalization and demoralization, little will be done to reverse policies and practices that continue today.

Public policy should be based on evidence, not popular perception, and our attention should shift to the real causes of the problems faced by a people who did nothing to deserve the hardships and indignities that have been continually heaped upon them.

A retired teacher, Mark DeWolf is a writer and musician living in Halifax. He is writing a memoir of his childhood on the Blood (Kainai) Reserve in Southern Alberta, and is a research associate at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.